There is a particular kind of authority that does not shake hands. It does not smile for photographs. It does not ask permission. It sits quietly inside budgets, bylaws, and blueprints, shaping outcomes long after applause has moved on. In The Power Broker, Robert Caro’s monumental 1974 study of Robert Moses, power is not performed—it is embedded.

This is not a business book. There are no lessons flagged in bold, no closing chapters urging self-improvement. And yet, for anyone interested in how control is actually accumulated and sustained, The Power Broker may be the most revealing text ever written. It is a study in unelected power—the kind that endures precisely because it avoids attention.

Caro introduces us to Moses not as a charismatic leader or visionary founder, but as an administrator. A man fluent in procedure. A master of authorities, commissions, and funding mechanisms that sounded dull enough to be ignored. Moses never ran for office, yet he reshaped New York more decisively than those who did. Roads carved through neighborhoods. Bridges dictated who could pass and who could not. Parks appeared where opposition once stood. All without speeches, campaigns, or slogans.

The opening revelation of The Power Broker is subtle but devastating: democracy is loud; power is quiet.

Caro’s prose moves deliberately, patient to the point of audacity, because the book is not about drama—it is about accumulation. Each chapter adds another layer of authority, another small adjustment to a system, until resistance becomes impractical. Moses does not conquer through force; he exhausts through structure. His genius, if it can be called that, lies in understanding that control over infrastructure eliminates the need for persuasion.

Entrepreneurs often misunderstand this. They chase influence instead of architecture. They build brands instead of systems. They seek visibility instead of inevitability. The Power Broker exposes this mistake without ever naming it.

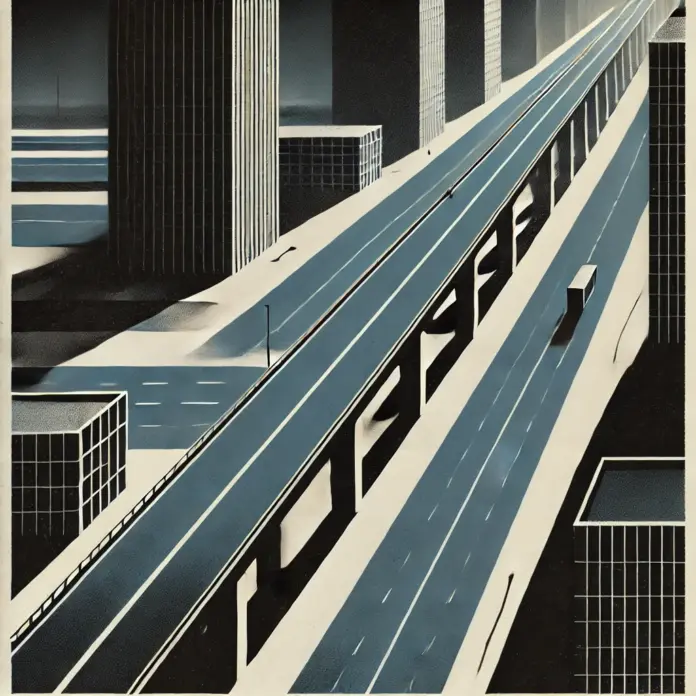

Moses understood that whoever controls the rails controls the direction of travel. Highways determined commerce. Zoning determined wealth. Financing authorities determined which ideas lived and which died. He did not need to win arguments because he decided the terms on which arguments could be made. That is unelected power at its most durable.

The cultural discomfort of The Power Broker lies in its refusal to flatter ambition. Moses is not presented as heroic, nor as a simple villain. He is something more unsettling: effective. His methods work. His systems endure. The cost—human, social, moral—is devastating, but it does not undo the efficiency of his control. Caro forces the reader to confront an uncomfortable truth: effectiveness and virtue are not the same thing.

For modern business readers, this is where the book sharpens. We live in an era that equates leadership with visibility. Founders are expected to be storytellers, performers, symbols. But Moses built power by disappearing into paperwork. He avoided applause because applause invites scrutiny. Scrutiny invites friction. Friction slows systems. Moses optimized for speed and permanence, not affection.

The empresario reads The Power Broker as a manual in negative space. What is not said matters more than what is. Moses rarely explains himself. He does not justify. He proceeds. His authority compounds because it is boring enough to be overlooked. Infrastructure, Caro shows us, is power that no longer needs permission.

This insight feels increasingly relevant in an age of platforms and protocols. The most powerful companies today do not argue loudly about culture; they control distribution. They set defaults. They write the fine print. They build systems that feel neutral while shaping behavior at scale. Moses would have understood this instinctively.

Yet Caro does not let us admire Moses comfortably. The book’s moral gravity comes from its attention to consequence. Entire communities are displaced. Neighborhoods are erased with bureaucratic indifference. The same systems that make power efficient also make it cruel. The Power Broker insists that we hold both truths at once: unelected power is durable—and dangerous.

This is what elevates the book beyond biography or history. It becomes a meditation on the architecture of control. Power that avoids applause avoids accountability. Power that embeds itself in systems survives personalities. And power that never has to ask for votes rarely listens.

For entrepreneurs, investors, and leaders, the lesson is not to imitate Moses’s ruthlessness, but to recognize where real leverage lives. Not in speeches. Not in branding. Not in charisma. But in the quiet mechanisms everyone else ignores.

In the end, The Power Broker is not warning us about corruption so much as it is correcting a misunderstanding. Power does not want to be seen. It wants to be permanent. And permanence, Caro reminds us, is built not on popularity—but on infrastructure.